Water Hammer In Hydraulics

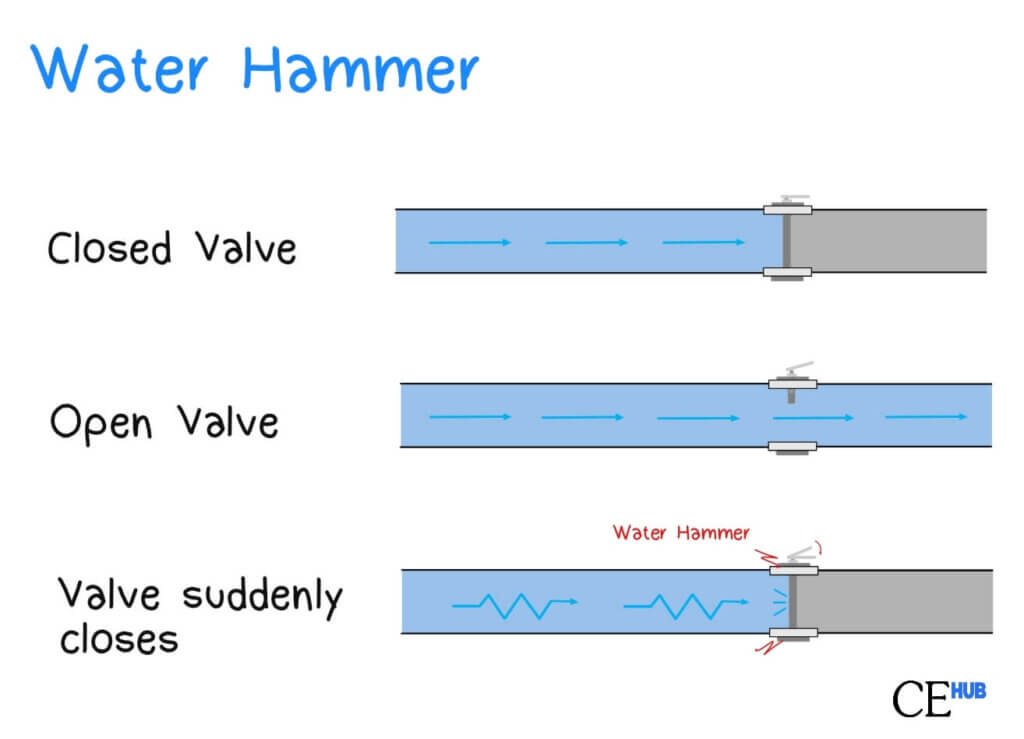

What is Water Hammer?

Water hammer, also known as hydraulic shock or hydraulic transient, is a pressure surge or wave phenomenon that occurs when a fluid in motion is suddenly forced to stop or change direction abruptly. This rapid change in flow velocity creates a shock wave that propagates through the piping system, potentially causing significant damage to pipes, valves, pumps, and other hydraulic components.

📌 Key Point: The term “water hammer” comes from the characteristic hammering sound that accompanies the pressure wave as it travels through the pipeline system. Despite its name, this phenomenon can occur with any liquid, not just water.

Water Hammer: Step-by-Step Analysis

Understanding water hammer requires analyzing how pressure waves travel through piping systems. Let’s build this understanding systematically.

Foundation: Newton’s Law and Momentum

Water hammer is fundamentally a momentum problem. When fluid flow suddenly stops, we must account for the momentum change:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The ratio represents the speed at which the pressure wave travels through the fluid, this is the acoustic wave speed or celerity of the fluid in the pipe.

![]()

Substituting the wave speed into our pressure equation:

![]()

Where:

ρ = fluid density

c = wave speed

Δv = velocity change

Step 1: Wave Speed in Rigid Pipes

We begin with the idealized case of a perfectly rigid pipe. The wave speed depends only on the fluid’s properties:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[C= \sqrt{\frac{E_B}{\rho}}\]](https://civilengghub.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-30a9bc59351e6dafc575ac45d9e61126_l3.png)

Where:![]()

![]()

![]()

The bulk modulus E_B represents the fluid’s resistance to compression; the higher the bulk modulus, the stiffer the fluid, and the faster pressure waves travel through it.

Step 2: Pipe Elasticity (for non-rigid)

In reality, pipes are not rigid. Under pressure, the pipe walls expand slightly, effectively making the fluid “easier to compress” from a system perspective. This requires modifying our wave speed equation.

We replace the fluid bulk modulus E_B with an equivalent bulk modulus E’_B that accounts for both fluid and pipe behavior:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[C= \sqrt{\frac{E'_B}{\rho}}\]](https://civilengghub.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-0341398b49eb6114a49dfd6e2d5fab1b_l3.png)

Notice this equation has the same form as the rigid pipe case, but now E’_B < E_B, which means the wave speed C will be lower in real pipes.

Step 3: Calculating the Equivalent Bulk Modulus

The equivalent bulk modulus combines two effects: fluid compressibility and pipe wall expansion.

![]()

Where:

D = pipe inner diameter (m)

E = elastic modulus of pipe material (Pa)

t = pipe wall thickness (m)

Based from the equation above, we can derive it so that we can get the direct form of the equivalent bulk modulus:

![]()

![]()

Where:

D = pipe inner diameter (m)

E = elastic modulus of pipe material

t = pipe wall thickness

Step 4: Time for the Pressure Wave to Travel

Now that we can calculate wave speed C, we can determine how long it takes for pressure disturbances to propagate through the system:

![]()

Where:

T = round-trip travel time

L = pipe length

Why 2L? When a valve closes, the pressure wave travels from the valve to the pipe end (L), reflects, and returns to the valve (L again), completing one cycle.

Common Causes of Water Hammer

- Rapid Valve Closure: Closing a valve too quickly is the most common cause, suddenly stopping fluid flow.

- Pump Startup or Shutdown: Sudden changes in pump operation can create significant pressure transients.

- Check Valve Slam: When check valves close rapidly due to flow reversal.

- Air Pockets: Trapped air can be compressed and released, causing pressure surges.

- Column Separation: When pressure drops below vapor pressure, creating voids that collapse violently.

Conclusion:

Water hammer remains one of the most critical considerations in hydraulic system design and operation. Understanding its causes, effects, and mitigation strategies is essential for engineers working with pipeline systems. Through proper design, appropriate protection devices, and careful operational procedures, water hammer can be effectively controlled, ensuring safe, reliable, and long-lasting hydraulic infrastructure.

As hydraulic systems become more complex and operate at higher pressures, the importance of comprehensive transient analysis continues to grow. Modern computational tools combined with time-tested engineering principles provide the means to design systems that safely handle the dynamic nature of fluid flow.

References:

Chaudhry, M. H. (2014). Applied hydraulic transients (3rd ed.). Springer.

Streeter, V. L., & Wylie, E. B. (1993). Fluid transients in systems. Prentice Hall.

Thorley, A. R. D. (2004). Fluid transients in pipeline systems: A guide to the control and suppression of fluid transients in liquids in closed conduits (2nd ed.). Professional Engineering Publishing.

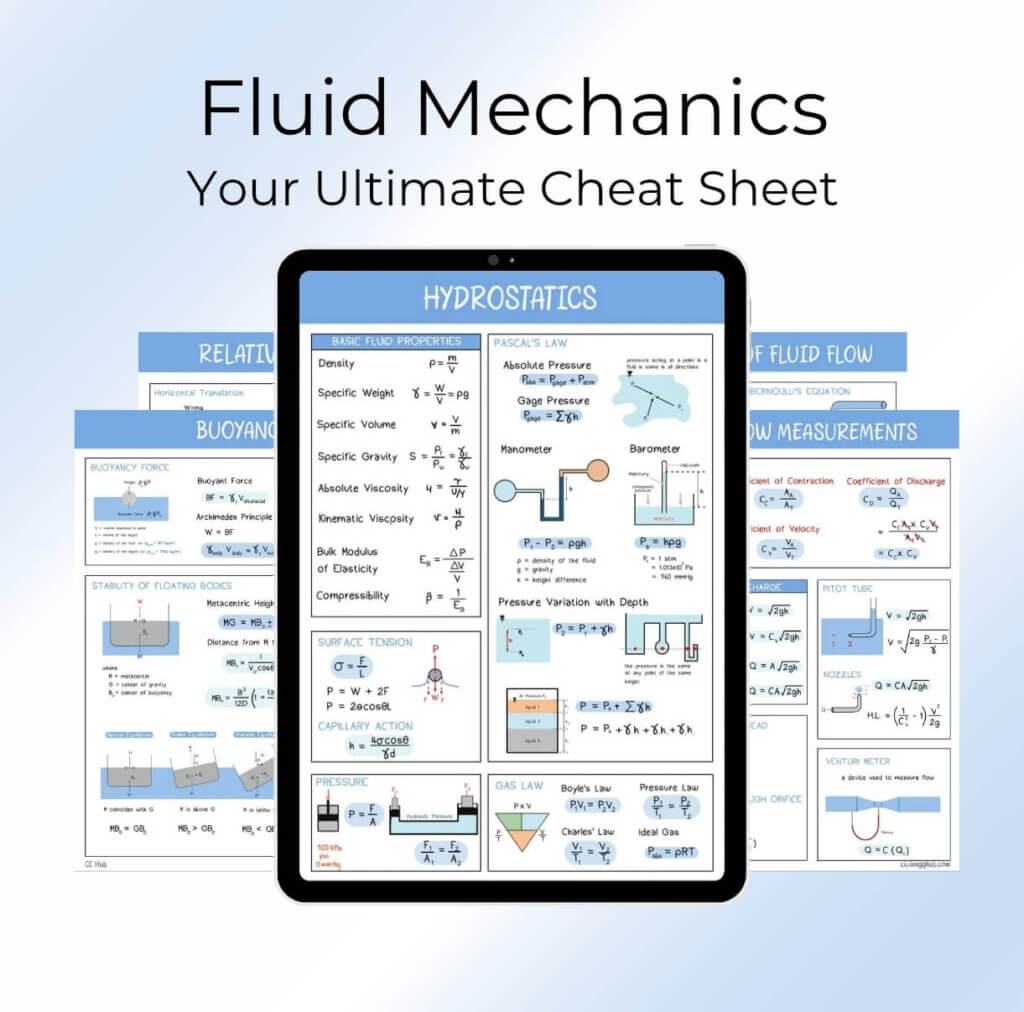

📍This post is part of FLUID MECHANICS COMPLETE Lessons. Also, if you want to avail the complete Cheat Sheet just click the ‘IMAGE” below.