Strain in Strength of Materials

Difference between Stress vs Strain

First, let’s understand the difference between stress and strain which a lot of students get confused.

Stress: Stress is fundamentally a measure of intensity. It describes how an internal force is distributed over a given area, rather than the force by itself. The same load can be harmless when spread over a large cross section and critical when concentrated into a small one.

Strain: on the other hand, is about deformation, it’s how much a material changes shape relative to its original size. When you pull on a rubber band, it stretches. That stretching, expressed as a ratio of the change in length to the original length, is strain. Strain is dimensionless because it’s a ratio of two lengths

Key Insights: Stress is the cause. and strain is the effect.

Types of Strain

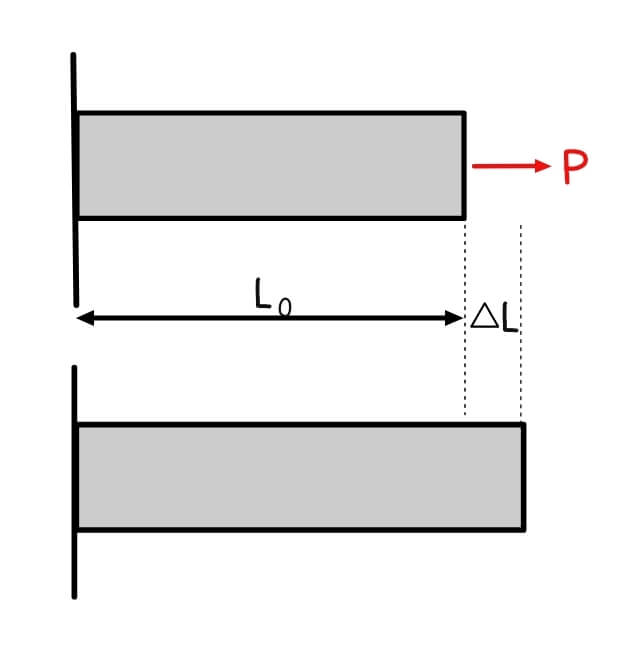

Tensile Strain: When Materials Stretch

Tensile strain is the deformation or elongation when a material is pulled or stretched. Think about a cable supporting an elevator or a tie rod in a truss. The formula for tensile strain is beautifully simple:

![]()

Where:

εₜ represents tensile strain

ΔL is the change in length

L₀ is the original length.

Note: When the material stretches, ΔL is positive, which means the strain is positive.

Compressive Strain: When Materials Compressed

Compressive strain happens when materials are compressed or shortened. A column supporting a building’s weight, a concrete cylinder in a testing machine, or the bottom fiber of a beam under load all experience compressive strain.

![]()

Note: when the material shortens, ΔL is negative, which means the strain is negative. The negative sign tells us immediately that we’re dealing with compression, not tension.

Volumetric Strain: Three-Dimensional Deformation

Real structures exist in 3D space, sometimes the volume change of a material matters just as much as its length change.

![]()

Where:

εᵥ is volumetric strain

ΔV is the change in volume

V₀ is the original volume.

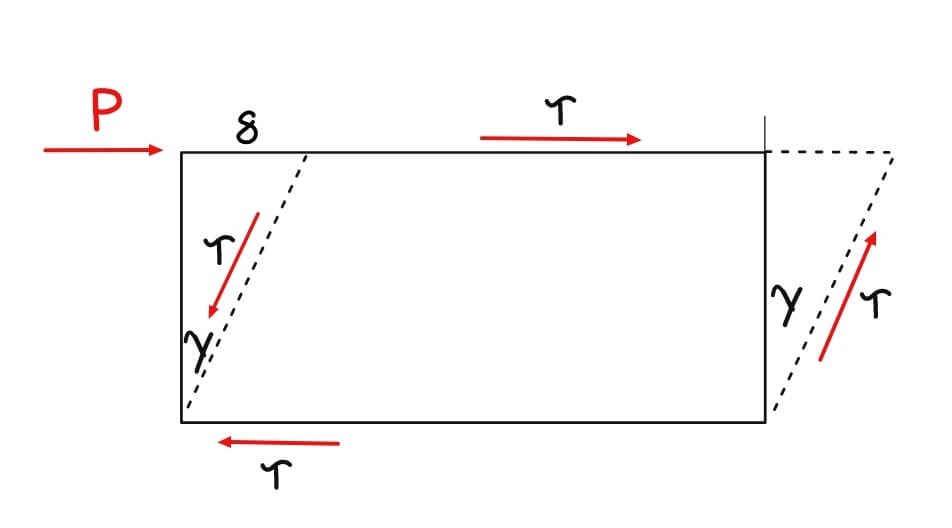

Shear Strain

Shear strain is different from the previous types because it doesn’t involve lengthening or shortening, it involves distortion. Picture a deck of cards: when you push the top card sideways while holding the bottom card fixed, the deck distorts into a parallelogram shape. That’s shear deformation.

![]()

Where:

γ (gamma) represents shear strain

δₛ is the shear deformation (the lateral displacement)

L is the height over which this displacement occurs.

Hooke’s Law: Relationship between Stress and Strain

A scientist name Robert Hooke discovered something remarkable in the 17th century: for many materials within a certain range, stress and strain are directly proportional.

![]()

Where:

σ (sigma) is the normal stress

E is the modulus of elasticity (also called Young’s modulus)

ε is the strain.

This equation tells us that if you double the strain, you double the stress (at least within the range of the material.

Note that E is like the material’s “resistance to deformation. A high E means the material fights back strongly against being deformed while a low E means more prone to deformation. Thus, we can express Hooke’s Law in terms of force and deformation.

![]()

Where

P is the axial force

A is the cross-sectional area

δ is the deformation

L is the length.

Rearranging the formulas, we can get the following:

Axial Strain

![]()

Axial Deformation

![]()

Shear Deformation and Shear Modulus

Just as normal stress and normal strain are related through the elastic modulus E, shear stress and shear strain are related through the shear modulus G:

[\tau = G\gamma]

This is essentially Hooke’s Law for shear.

Where:

τ is shear stress

G is the shear modulus (also called the modulus of rigidity)

γ is the shear strain.

The formula of shear deformation is:

![]()

where:

V is the shear force

L is the length (or height) over which shear occurs

A is the area

G is the shear modulus.

E&G Relationship

The elastic modulus E and the shear modulus G aren’t independent properties. They’re related through Poisson’s ratio:

![]()

Poisson’s ratio describes how much a material contracts laterally when stretched axially (or expands laterally when compressed axially).

The Stress-Strain Diagram: Understanding Material Behaviour

To understand stress and strain, you need to know about the stress-strain diagram (also called the stress-strain curve). This is a graph where we plot stress on the vertical axis and strain on the horizontal axis as we gradually increase the load on a test specimen.

1. Elastic Region: This is the initial straight-line portion where stress and strain are proportional (Hooke’s Law applies). If you unload the material in this region, it returns to its original shape with no permanent deformation. The slope of this line is the modulus of elasticity E.

2. Yield Point: This is where the material begins to deform plastically. For steel, there’s often a distinct yield point where the material suddenly yields with little increase in stress. The stress at this point is called the yield strength.

3. Plastic Region: Beyond the yield point, the material undergoes permanent deformation. Even if you remove the load, the material won’t return to its original shape. The material continues to deform at an increasing rate.

4. Strain Hardening: After initial yielding, many materials become stronger and can support higher stresses as deformation continues. This is called strain hardening or work hardening.

5. Necking and Fracture: Eventually, the specimen develops a localized reduction in cross-sectional area (necking) and ultimately fractures.

References:

Beer, F. P., Johnston, E. R., DeWolf, J. T., & Mazurek, D. F. (2015). Mechanics of materials (7th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

Gere, J. M., & Goodno, B. J. (2013). Mechanics of materials (8th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Hibbeler, R. C. (2017). Mechanics of materials (10th ed.). Pearson Education.