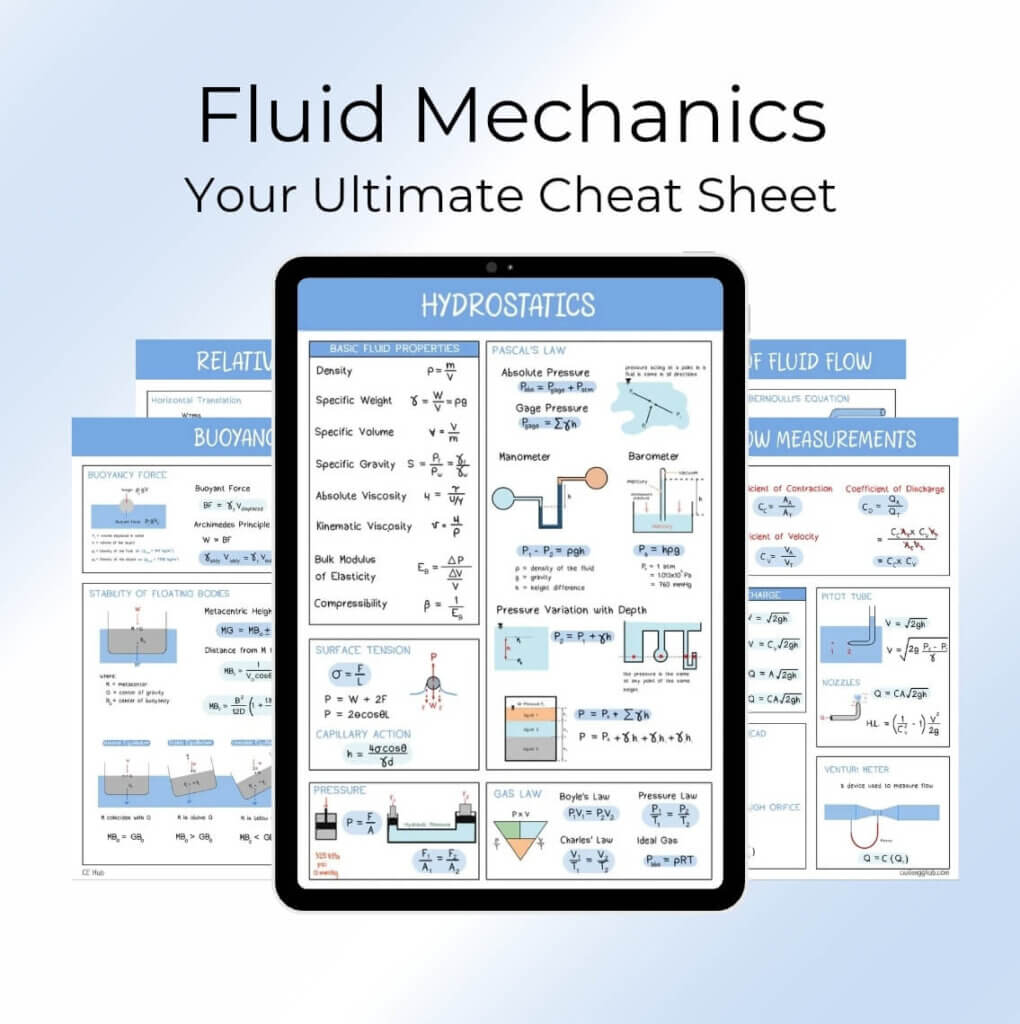

Fluid Mechanics and Hydraulics

What is Fluid Mechanics?

Fluid Mechanics In Civil Engineering, is taught in schools for us to understand how fluids behave may it be liquids or gases, and whether the fluid is at rest or in motion. For engineering students it’s one of the basic subjects you’re introduced to early on, and for good reason. Knowledge about fluid behavior is of fundamental importance to mechanical, civil, chemical, and many other fields of engineering.

BY DEFINITION

Fluid Mechanics is a branch of engineering that with the properties of the fluid at rest or in motion.

In the context of Fluid Mechanics In Civil Engineering, understanding fluid behavior is crucial for designing structures that interact with water, such as bridges and dams. So this roadmap of Fluid Mechanics will guide you to cover all the necessary topics in the course.

At its core, fluid mechanics is split into two parts:

Fluid Statics

Deals with fluid in rest.

Fluid Dynamics

Deals with fluid in motion

Fundamental Properties of Fluids

Before analyzing fluid motion or forces, it is essential to understand the basic physical properties of fluids. These properties control how fluids respond to external forces, temperature, and pressure.

Topics in this section explain viscosity, density, surface tension, capillary action, and gas behavior, which form the base for all later concepts in fluid mechanics.

Ch1: Fluid Properties

- Density is the ratio of mass of fluid and its volume.

- Specific weight is the weight of the fluid per unit volume.

- Specific Gravity is the ratio of density of a substance to the density of water.

Ch1.2: Surface Tension and Capillary Height

- Surface tension is the tendency of fluid surfaces to minimize their surface area and behave as if covered by an elastic membrane.

- Capillary action is the ability of a liquid to flow in narrow spaces without external forces, driven by the combined effect of cohesion and adhesion.

Ch 1.3: Gas Laws

Fluid Statics (Hydrostatics)

Fluid statics deals with fluids at rest and focuses on pressure variation, force distribution, buoyancy, and stability. These principles are crucial for the design of retaining structures and hydraulic installations.

This section explains how pressure acts on submerged surfaces, how floating bodies achieve equilibrium, and how fluids behave under acceleration or rotation

Ch 2: Hydrostatic Pressure

- Hydrostatic pressure is the pressure exerted by a fluid at rest due to its weight.

- The pressure at an point of a static homogenous fluid is the same in all directions.

- Atmospheric Pressure is the pressure exerted by the atmosphere. It varies with altitude and weather conditions.

- Absolute pressure is measured relative to a perfect vacuum, meaning it includes atmospheric pressure.

- Gauge pressure is the pressure measured relative to atmospheric pressure. It indicates the pressure above or below the atmospheric level.

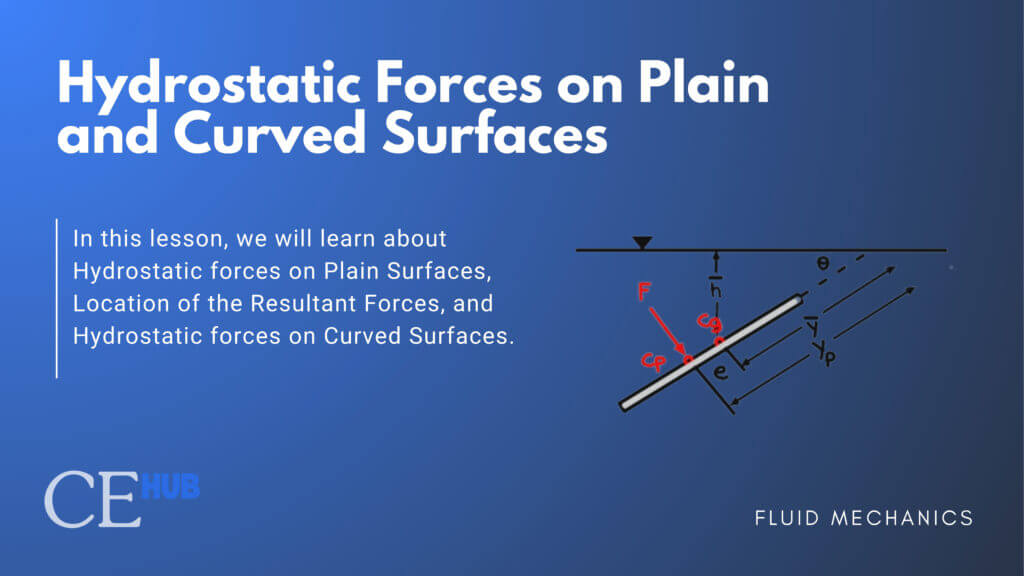

Ch 3: Hydrostatic Forces

- Hydrostatic Forces on Plain Surface: Submerged surfaces experience pressure forces that vary with depth.

- Hydrostatic Forces on Curved Surface

- Moment of Inertia along the Neutral Axis

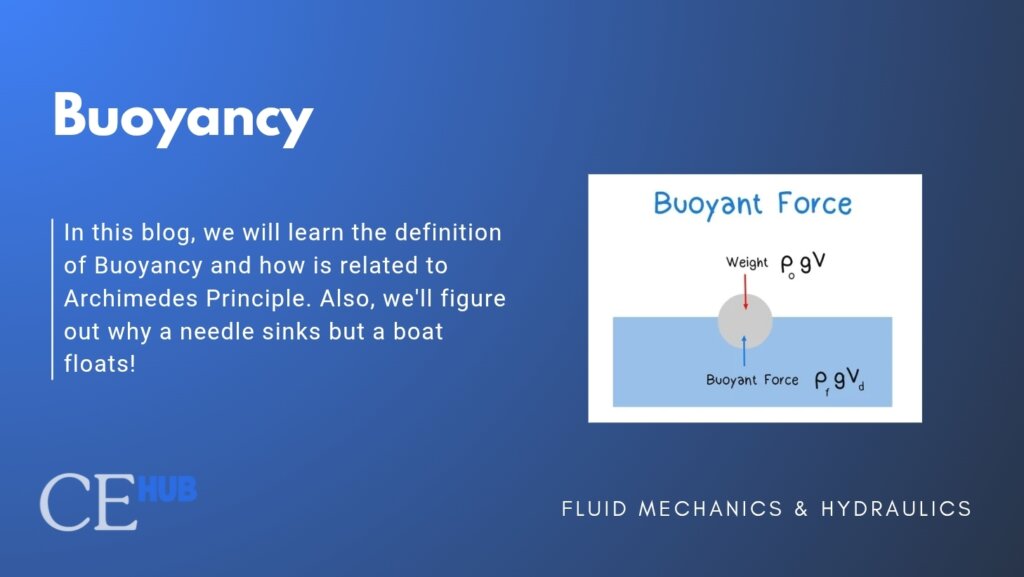

Ch 4: Buoyancy

- Buoyancy is the upward-directed force a fluid exerts on an object that’s been immersed into it.

- Archimedes’ Principle: Any object completely or partially submerged in a fluid experiences an upward force (buoyant force) equal to the weight of the fluid displaced by the object.

Key Formula:

- Buoyant Force:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[FB = ρ_{fluid} × g × V_{displaced}\]](data:image/gif;base64,R0lGODdhAQABAPAAAMPDwwAAACwAAAAAAQABAAACAkQBADs=)

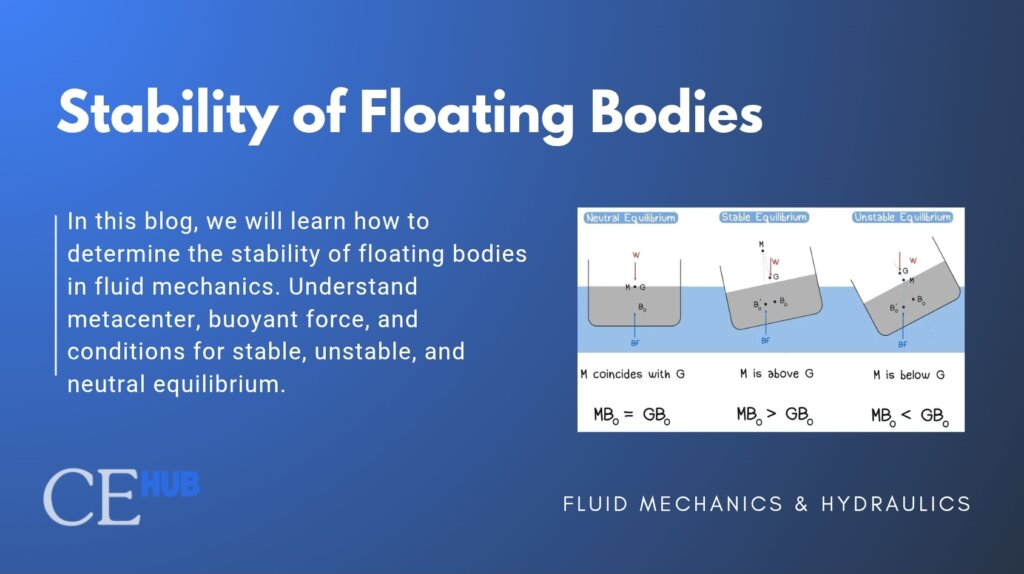

Ch 5: Stability of Floating Bodies

- Types of Stability: Stable, Neutral and Unstable Equilibrium

- Center of Gravity and Center of Buoyancy

- Metacentric Height: Floating vessels remain stable when their metacentric height is positive.

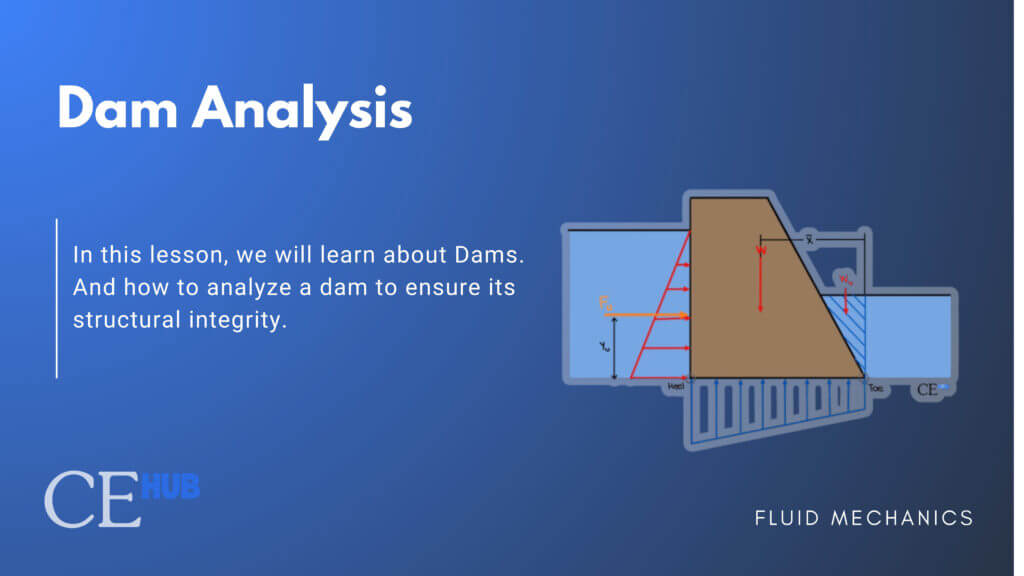

Ch 6: Dam Analysis

- Overturning: Factor of Safety = Resisting Moment / Overturning Moment

- Sliding: Factor of Safety = Friction Force / Horizontal Force

- Foundation Pressure

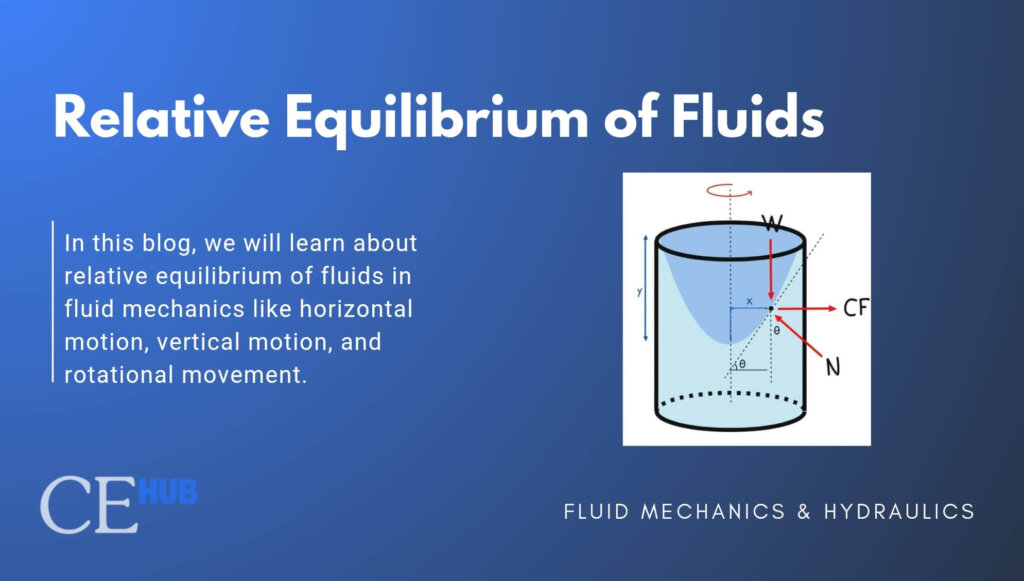

Ch 7: Relative Equilibrium of Fluids

- Horizontal Translation, Inclined Translation, and Vertical Translation

- Rotational Translation

- Cases of overflow

Basic Fluid Dynamics

This section introduces the fundamental equations that govern fluid motion. These equations describe how velocity, pressure, and energy change along a flow path.

Understanding these principles is essential for pipe flow analysis, flow measurement, and hydraulic machinery.

Ch 8: Bernoulli’s Equation

- Bernoulli Equation states that in a steady, incompressible, and frictionless flow, the total mechanical energy of the fluid remains constant along a streamline.

- Energy cannot be created or destroyed—only transferred.

- Bernoulli’s Equation with Correction Factor

Ch 9: Pumps and Turbines (Bernoulli)

- Pumps are mechanical devices that add energy to a fluid system.

- Turbines are also mechanical devices but contrary to the pumps, they extract energy.

- Power is the rate at which energy is transferred or work is done

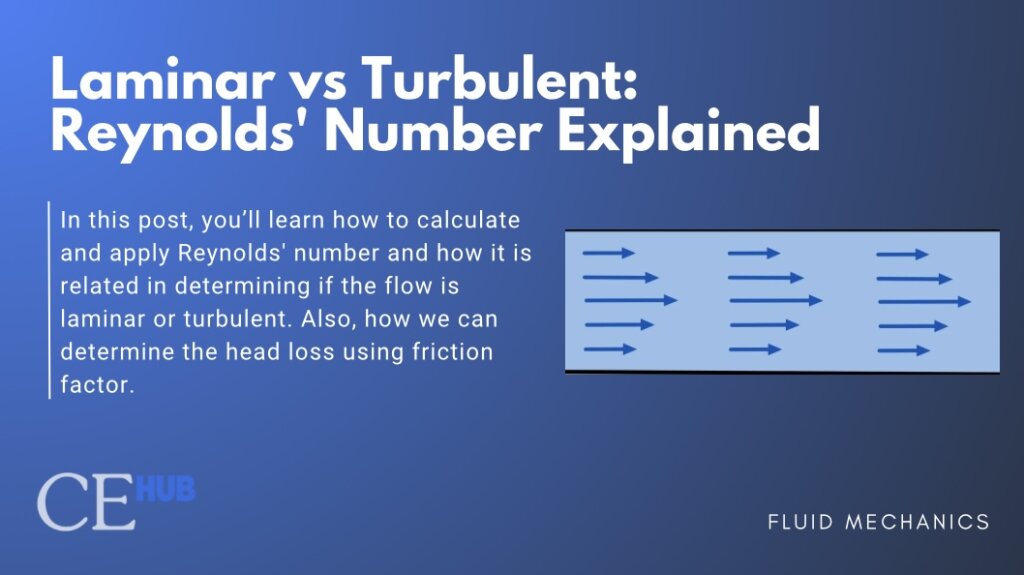

Ch 10 : Reynold’s Number

- Reynold’s Number (Re) predicts whether a flow is laminar or turbulent. It’s a dimensionless number comparing inertial and viscous forces.

- Laminar flow is smooth and orderly. Fluid particles flow linearly. In parallel layers with no crossing of paths.

- Turbulent flow is chaotic. Fluid particles swirl and move in random paths, known as eddies.

- Head loss is related to the flow and the properties of the pipe according to the Darcy-Weisbach equation:

Ch 11: Continuity Equation

- Continuity Equation is derived from mass conservation. What goes in (Mass of Fluid Entering) is equal to what goes out (Mass of fluid leaving).

- Discharge is the volumetric flow rate of liquid which equals to the volume of liquid passing through a given cross-sectional area per unit of time.

Flow Measurement

Accurate flow measurement is essential for hydraulic design and system control. This section focuses on devices and structures used to measure discharge in pipes and open channels.

These principles are widely used in laboratories, irrigation systems, and water treatment facilities.

Ch 12: Fluid Flow Measurement

- Device Coefficients: Coefficient of Contraction, Coefficient of Velocity, Coefficient of Discharge.

- Venturi Meters: features a gradual contraction (convergent cone), throat section, and gradual expansion (divergent cone), designed to minimize energy losses.

- Pitot Tube: measures local velocity by comparing stagnation pressure to static pressure.

- Flow Nozzles: is a smooth, contoured restriction that combines features of orifices and venturi meters. It provides better accuracy than orifices with less pressure loss, at moderate cost.

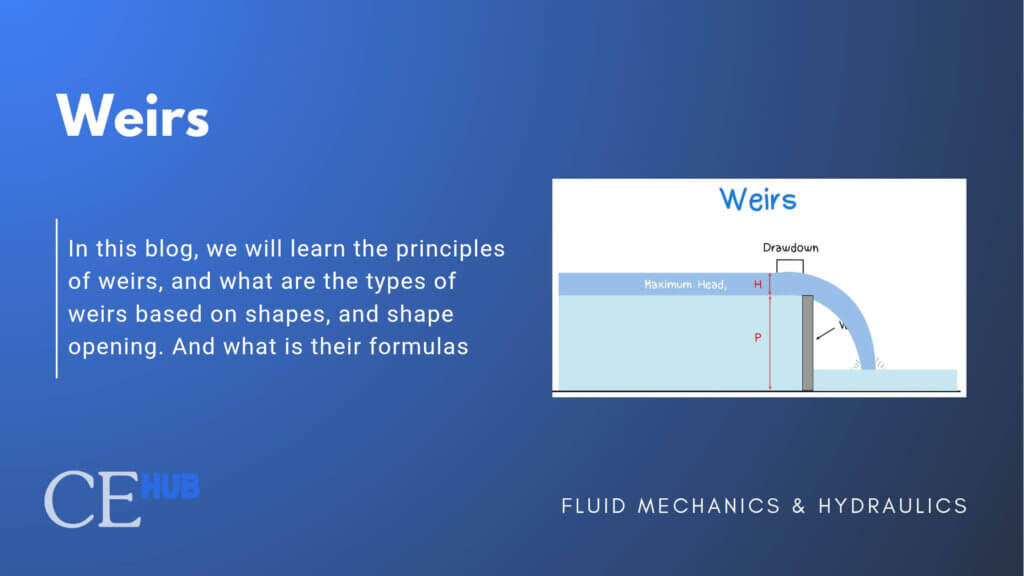

Ch 13: Weirs

- Weir is a low dam or barrier built across a river or channel to control water flow.

- Types of Weir: Rectangular Weir, Triangular Weir, Trapezoidal Weir

Open Channel Flow

Open channel flow deals with fluids that have a free surface exposed to the atmosphere. This is a major branch of fluid mechanics used in canals, rivers, and drainage systems.

The topics in this section explain flow classification, efficiency of channel sections, and rapidly varied flow phenomena.

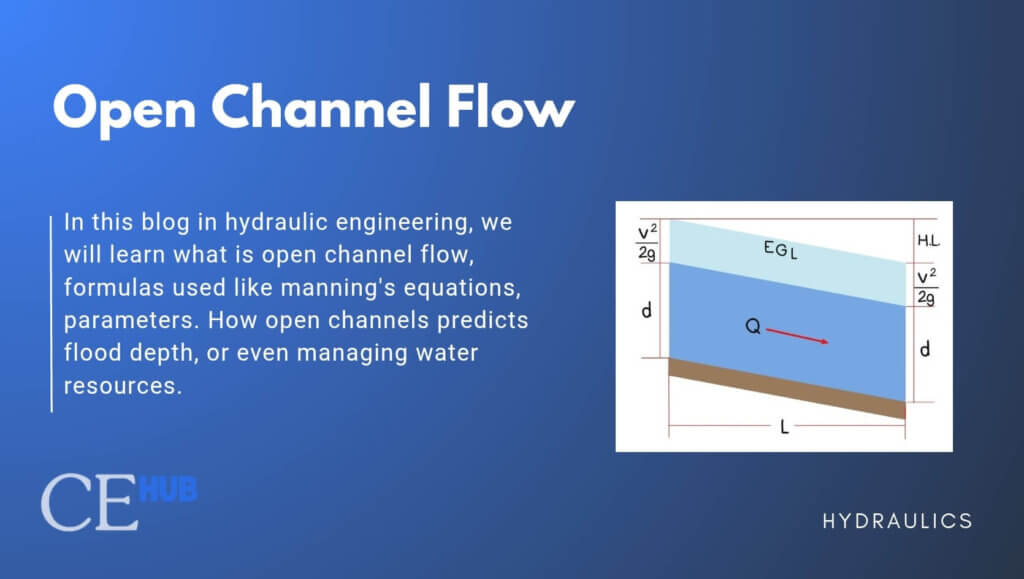

Ch 14: Open Channel Flow

- Open Channel flow is the movement of water through a channel where at least one surface (the top) is exposed to atmospheric pressure.

- Critical Flow represents a unique equilibrium state where specific energy reaches its minimum value.

- Hydraulic Radius is defined as the cross-sectional area of flow divided by the wetted perimeter:

Ch 15: Most Efficient Sections

- Optimal channel shapes minimize construction costs by reducing wetted perimeter for a given area.

- Most efficient rectangular: Width = 2 × Depth

Ch 16: Froude Number

- Dimensionless parameter classifying open channel flow regimes.

- Froude Number: Fr = V/√(gy)

- Fr < 1: Subcritical (tranquil) flow

- Fr = 1: Critical flow

- Fr > 1: Supercritical (rapid) flow

Pipe Flow

Pipe flow analysis is one of the most important applications of fluid mechanics in civil engineering. This section covers the behavior of fluids in closed conduits, energy transfer through machines, and transient flow effects.

These topics are directly applicable to water supply networks, pumping stations, and hydraulic pipelines.

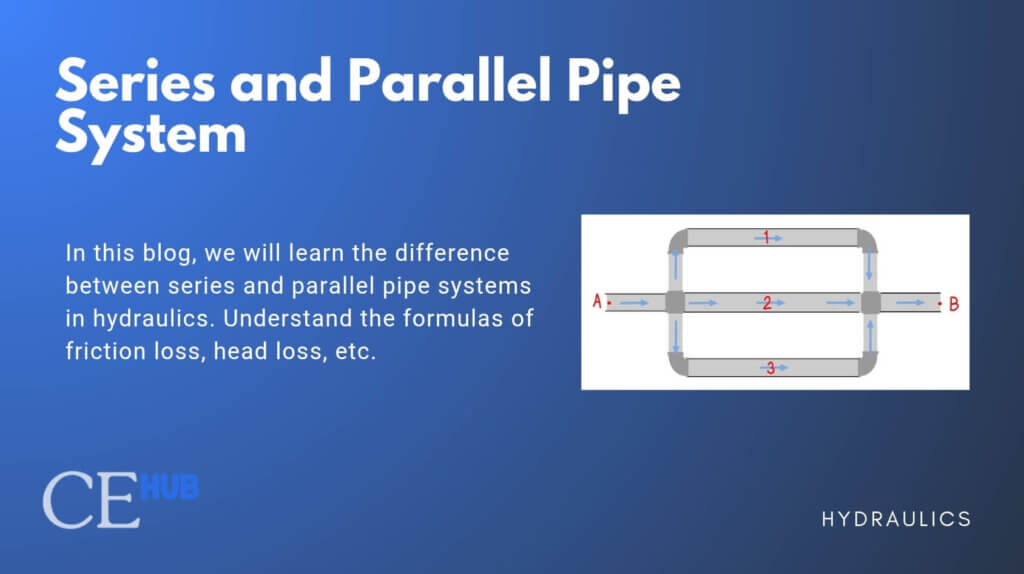

Ch 17: Series and Parallel Pipe System

- Series: Same flow, head losses add (hL_total = hL1 + hL2 + …)

- Parallel: Same head loss, flows add (Q_total = Q1 + Q2 + …)

Ch 18: Reservoir

Ch 19: Hydraulic Jump

- Hydraulic Jump occurs when rapidly flowing water at a shallow depth suddenly transitions to slowly flowing water at a greater depth.

- Momentum Equation states that the change in momentum equals the net force acting on the control volume.

Ch 21: Forces on Vanes

- Momentum analysis determines forces when fluid jets strike moving or stationary vanes.

- Force: F = ρQ(V₁ – V₂) = ṁΔV

Want to have the Complete Fluid Mechanics Cheat Sheet?