Gas Laws: An Engineering Guide 2026

When analyzing any gas system, e need to track four fundamental parameters:

Pressure (P): This represents the force per unit area that gas molecules exert on container walls through molecular collisions. Higher collision frequency means higher pressure.

Temperature (T): In thermodynamic terms, temperature indicates the available thermal energy that converts into molecular kinetic energy. Hotter gases have faster-moving molecules.

Volume (V): Simply put, this is the physical space the gas occupies within its container.

Quantity (n): Measured in moles, this tells us how many molecules we’re dealing with in our system.

Boyle’s Law: The Pressure-Volume Relationship

Robert Boyle discovered that when you keep temperature and quantity constant, pressure and volume exhibit an inverse relationship.

The Law: At constant temperature, the pressure and volume of a gas are inversely proportional.

The mathematical expression is:

![]()

Consider a piston system: if you compress the gas to half its original volume, the pressure doubles. Why? The molecules travel shorter distances between wall collisions, resulting in more frequent impacts per unit time. This inverse proportionality is critical for designing pneumatic systems, compressors, and hydraulic equipment.

Key point: Temperature must remain constant for this law to apply.

Charles’ Law

Jacques Charles established that volume and absolute temperature maintain a direct proportional relationship when pressure and quantity remain fixed.

The Law: At constant pressure, the volume of a gas is directly proportional to its absolute temperature.

The equation is:

![]()

Think about heating a balloon. As thermal energy increases, molecules move faster. To maintain constant pressure (constant collision frequency with walls), the container must expand. Double the absolute temperature, and you’ll double the volume. This principle is fundamental in thermal expansion calculations and HVAC system design.

Important note: Temperature must be in Kelvin (K), not Celsius or Fahrenheit.

Gay-Lussac’s Law: The Pressure-Temperature Relationship

The Law: At constant volume, the pressure of a gas is directly proportional to its absolute temperature.

![]()

What it means: As temperature increases, so does pressure (if the container doesn’t expand).

Real-world example: This is why aerosol cans have warnings not to expose them to heat or fire. As the temperature rises, the pressure inside the can increases, potentially causing an explosion.

Combined Gas Law

This synthesis of Boyle’s and Charles’s laws is particularly useful when analyzing gas behavior through state changes. For instance, calculating final pressure when both temperature and volume change in a closed system.

The Law: This combines Boyle’s, Charles’s, and Gay-Lussac’s laws into one powerful equation.

![]()

What it means: This equation relates pressure, volume, and temperature all at once, allowing you to calculate changes when multiple variables are changing simultaneously.

When to use it: The combined gas law is your go-to equation when you’re dealing with situations where pressure, volume, AND temperature are all changing. It’s incredibly versatile.

If one variable stays constant, the combined gas law simplifies back to one of the individual laws:

- If temperature is constant → Boyle’s Law

- If pressure is constant → Charles’s Law

- If volume is constant → Gay-Lussac’s Law

Ideal Gas Law: Universal Equation

The ideal gas law describes the relationship between all the properties of an ideal gas. Unlike the other laws we’ve discussed, this equation allows you to calculate the absolute values of these properties, not just how they change.

Use the ideal gas law when you need to find one property of a gas (like pressure, volume, temperature, or amount) when you know the other three. It’s especially useful for calculating how many moles of gas you have or predicting the behavior of gases in chemical reactions.

![]()

Where:

P = Pressure

V = Volume

n = number of moles of gas

R = Universal Gas Constant (8.314 J/mol·k)

T = Temperature in Kelvin

Conclusion:

Gas laws might look like just another set of formulas we had to memorize, but they’re actually describing stuff that matters in our daily work. When you’re dealing with pneumatic systems on a construction site, checking tire pressure on heavy equipment, or understanding how temperature swings affect confined spaces in tunnels and underground utilities, you’re working with these principles whether you realize it or not.

As civil engineers, we see this constantly. Compressed air tools, HVAC design for buildings, soil gas behavior in contaminated site remediation, it all comes back to how gases respond to pressure and temperature changes. If you’re working in water treatment or environmental engineering, you’re dealing with gas behavior in aeration systems and chemical processes.

Once you really get these laws, not just memorize them but understand what’s actually happening, you start seeing them everywhere. You’ll think about partial pressures when troubleshooting, or consider thermal expansion in your designs. It becomes second nature.

References:

Evett, J. B., & Liu, C. (1994). 2500 Solved Problems in Fluid Mechanics and Hydraulics.

Petrucci, Ralph H. General Chemistry: Principles and Modern Applications. 9th Ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2007.

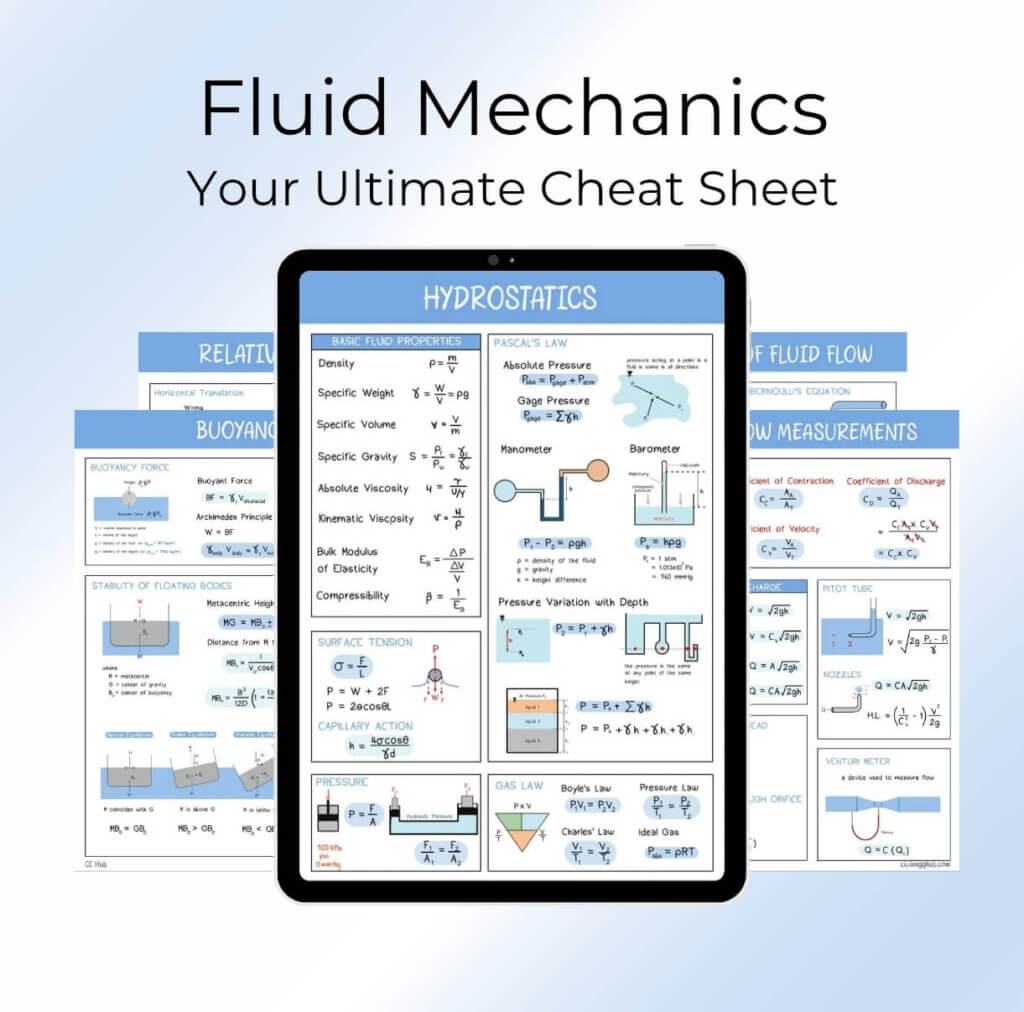

📍This post is part of FLUID MECHANICS COMPLETE Lessons. Also, if you want to avail the complete fluid mechanics formulas just click the image below.