Surface Tension and Capillary Action

What is Surface Tension?

Surface tension is the tendency of fluid surfaces to minimize their surface area and behave as if covered by an elastic membrane. At the molecular level, this phenomenon arises from the cohesive forces between liquid molecules. Molecules in the bulk of a liquid are surrounded by neighbors on all sides, experiencing balanced intermolecular forces. However, molecules at the surface have neighbors only on one side and below, creating a net inward force that pulls surface molecules toward the bulk.

What Causes Surface Tension?

The molecular basis of surface tension lies in intermolecular forces, primarily Van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonding, and electrostatic interactions. In liquids like water, hydrogen bonding between molecules creates particularly strong cohesive forces. When a molecule moves from the interior to the surface, work must be done against these cohesive forces, increasing the potential energy of the system.

Mathematically, surface tension can be expressed as:

![]()

Where:

σ = Surface Tension

F = Force in Newtons

L = Length in Meters

This Table shows that the higher the temperature is, the lower the surface tension. Therefore, they are inversely proportional.

Pressure in Spherical Droplets

How does surface tension create pressure differences? Consider a spherical water droplet suspended in air. The surface tension acts along the entire surface, pulling inward uniformly from all directions. This inward pull must be balanced by a higher pressure inside the droplet compared to the outside.

For a spherical droplet or bubble where both principal radii are equal (R₁ = R₂ = R), the Young-Laplace equation simplifies to:

For a spherical droplet or bubble where R₁ = R₂ = R, this simplifies to:

![]()

or in terms of diameter

![]()

General Pressure Relationship

For liquid surface, the total pressure can be expressed as:

![]()

This can be related to surface tension as:

![]()

Where:

L = length of the surface

Capillary Action

Capillary action is the ability of a liquid to flow in narrow spaces without external forces, driven by the combined effect of cohesion and adhesion. This phenomenon is described through force equilibrium and surface tension effects.

We said that surface tension is defined as force per unit length:

![]()

Capillary Rise in Tubes

How does surface tension cause liquids to climb up narrow tubes against gravity? When a narrow tube is inserted into a liquid, surface tension acts along the contact line where the liquid, tube wall, and air meet. This surface tension force pulls upward on the liquid, creating the familiar meniscus shape.

For capillary action in a circular tube, we analyze the vertical force balance. The upward pull from surface tension must support the weight of the liquid column that rises in the tube:

![]()

![]()

![]()

Substituting the weight and the surface tension

![]()

![]()

![]()

Where:

h = height of liquid rise or depression

σ is surface tension

θ is the contact angle

γ is the specific weight of the liquid (ρg)

D is the diameter of the tube

Important Note: The capillary rise or fall depends on the adhesion between the liquid and solid surface.

For water in a glass capillary tube, the contact angle is small (good adhesion), resulting in upward capillary rise. Mercury, with its large contact angle with glass (poor adhesion), exhibits capillary depression instead.

Capillary Rise between Two Parallel Plates

If it is two plates, the force balance is:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

For two plates separated by distance d and width x:

![]()

Solving for the height:

![]()

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the difference between surface tension and capillary action?

Surface tension is the cohesive force that causes liquid surfaces to contract and behave like an elastic membrane, allowing objects like water striders to walk on water. Capillary action, on the other hand, is the ability of a liquid to flow through narrow spaces without external forces, caused by the combination of surface tension and adhesive forces between the liquid and surrounding surfaces. While surface tension occurs at any liquid-air interface, capillary action specifically happens in tubes, porous materials, or narrow gaps.

2. Why does water rise in a capillary tube but mercury falls?

Water rises in a capillary tube because its adhesive forces to the glass are stronger than its cohesive forces (water molecules attracting each other), creating a concave meniscus that pulls the liquid upward. Mercury, however, has stronger cohesive forces than adhesive forces to glass, forming a convex meniscus that pushes downward. This is why mercury appears to be “repelled” by the glass tube and sits lower inside the tube than outside it.

3. What factors affect the height of capillary rise in a tube?

The height of capillary rise depends on several key factors: the surface tension of the liquid (higher surface tension produces greater rise), the radius of the tube (narrower tubes result in higher rise), the density of the liquid (denser liquids rise less), the contact angle between liquid and tube material (smaller angles increase rise), and gravity. The relationship is described by the Jurin’s Law equation: h = (2γ cos θ)/(ρgr), where smaller tube radius and higher surface tension lead to increased capillary height.

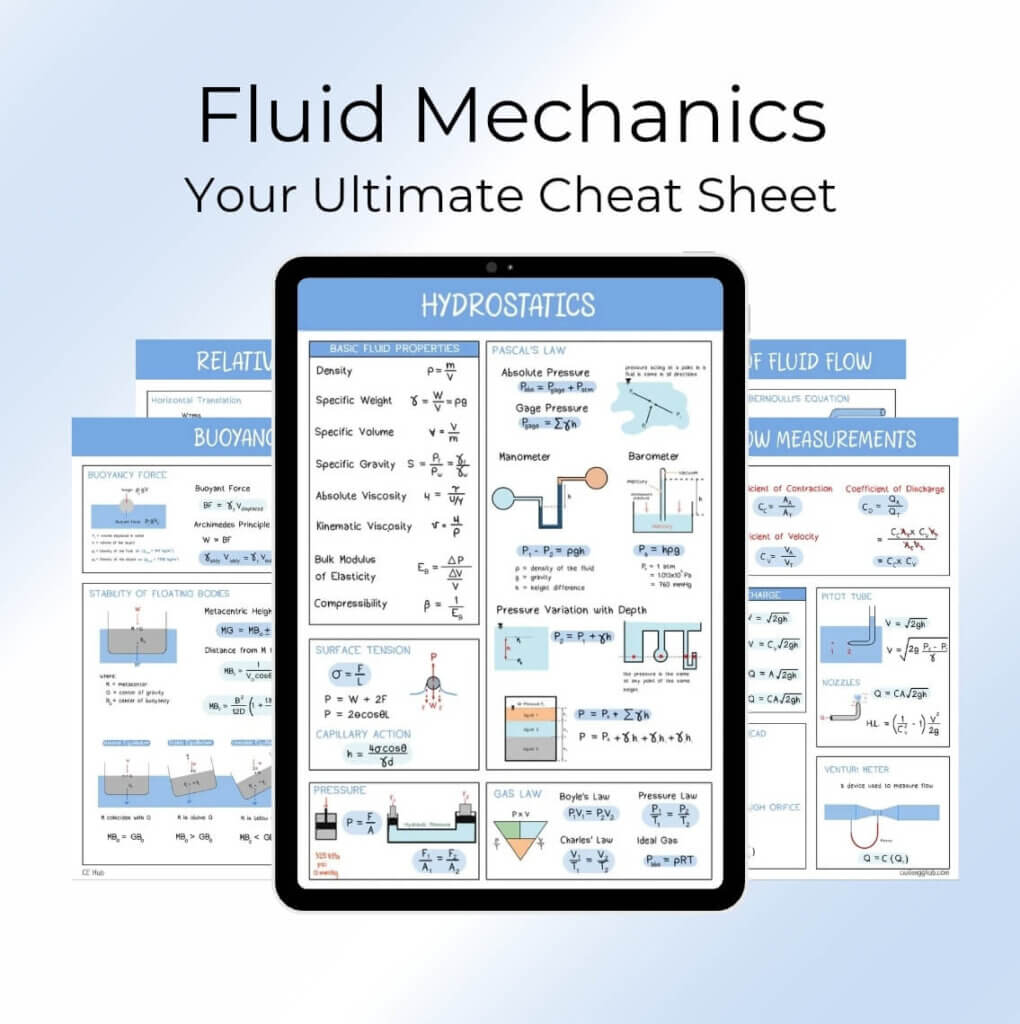

📍This post is part of FLUID MECHANICS COMPLETE Lessons. Also, if you want to avail the complete Cheat Sheet just click the “image” below.

References:

Adamson, A. W., & Gast, A. P. (1997). Physical chemistry of surfaces (6th ed.). Wiley-Interscience.

White, F. M. (2016). Fluid mechanics (8th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.