Viscosity in Fluid Mechanics

What is Viscosity?

Viscosity is the property of a fluid that represents its resistance to flow or deformation. It is essentially the internal friction within a fluid that arises when adjacent layers of fluid move at different velocities.

Think of it as the “thickness” or “stickiness” of a fluid, though these everyday terms don’t fully capture the precise scientific meaning. But first, let’s understand the phenomena behind viscosity.

Shear Stress in Flowing Fluids

When fluid layers move at different velocities relative to each other, shear stresses emerge between them. This phenomenon resembles friction between sliding solid surfaces, but with distinct characteristics unique to fluid behavior.

The most pronounced effects of shear stress occur near solid boundaries. At a wall interface, the boundary exerts significant shear on adjacent fluid particles, forcing them to zero velocity, a fundamental principle known as the no-slip condition. This shear propagates through successive fluid layers, decelerating flow near the wall and creating a characteristic velocity gradient.

Understanding Velocity Profiles and Shear Stress Distribution

The relationship between shear stress magnitude and velocity profile slope (du/dy, where u represents fluid velocity and y is wall distance) is crucial for flow analysis. In the free stream region, fluid layers travel at nearly identical velocities, producing minimal velocity gradients and consequently small shear stresses. Conversely, near-wall regions exhibit rapid velocity changes, resulting in steep gradients and substantial shear stresses.

Newton’s Law of Viscosity

For the majority of fluids, shear stress and velocity gradient maintain a linear relationship. The proportionality constant in this relationship is what we call dynamic viscosity, typically denoted by the Greek symbol μ (mu) in engineering practice.

Viscosity functions as internal friction within moving fluids, working to minimize velocity differences by generating shear stresses proportional to velocity gradients. This relationship is mathematically expressed as:

![]()

Where:

τ is the shear stress (force per unit area, Pa or N/m²)

μ is the dynamic viscosity (Pa·s or N·s/m²)

This equation reveals that shear stress is directly proportional to the velocity gradient, with viscosity as the proportionality constant. The higher the viscosity, the greater the stress required to achieve a given rate of deformation.

Types of Viscosity

Dynamic Viscosity

Also called the absolute viscosity, represents the internal resistance to flow.

Kinematic Viscosity

Kinematic viscosity is the ratio of dynamic viscosity to fluid density, it is represented by the greek letter (nu).

![]()

Where:

ν is kinematic viscosity

μ is dynamic viscosity

ρ is fluid density

Note:

1 poise = 0.1 Pa-sec

1 stoke = 0.0001 m^2/s

Newtonian vs. Non-Newtonian Fluids

Newtonian Fluids

Fluids that obey Newton’s law of viscosity are called Newtonian fluids. For these fluids, viscosity remains constant regardless of the shear rate (velocity gradient). The relationship between shear stress and shear rate is linear and passes through the origin.

Examples are:

- Water

- Air

- Most Gases

- Light Oils

- Glycerin

Non-Newtonian Fluids

Non-Newtonian fluids do not follow Newton’s law of viscosity. Their apparent viscosity changes with the applied shear rate or stress. These fluids exhibit complex behavior and are classified into several categories:

- Shear-Thinning (Pseudoplastic) Fluids

These fluids decrease in viscosity as shear rate increases. The fluid becomes “thinner” when stirred or agitated.

Examples are:

– Ketchup (flows easily when shaken)

– Paint (spreads easily when brushed)

-Blood - Shear-Thickening (Dilatant) Fluids

These fluids increase in viscosity as shear rate increases. The fluid becomes “thicker” under stress.

Examples are:

– Cornstarch and water mixture (oobleck)

– Quicksand

– Some concentrated suspensions - Bingham Plastics

These fluids behave as solids until a threshold yield stress is exceeded, after which they flow like Newtonian fluids.

Examples are:

– Toothpaste

– Mayonnaise

– Some Gels - Thixotropic Fluids

Viscosity decreases over time under constant shear stress, and the fluid recovers its viscosity when at rest.

Examples are:

– Some paints

– Yogurt

– Crude oil

Dimensional Analysis and Reynold’s Number

The Reynolds number is the most important dimensionless parameter involving viscosity:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the difference between Dynamic Viscosity and Kinematic Viscosity?

Absolute viscosity (also called dynamic viscosity) measures a fluid’s internal resistance to flow and shear stress, typically expressed in Pascal-seconds (Pa·s) or centipoise (cP). Kinematic viscosity, on the other hand, is the ratio of absolute viscosity to the fluid’s density, measuring how fast the fluid flows under gravity alone, expressed in square meters per second (m²/s) or centistokes (cSt). In simple terms, absolute viscosity tells you how thick a fluid is, while kinematic viscosity tells you how quickly that thick fluid will flow. The relationship is: kinematic viscosity = absolute viscosity / density.

2. Why does viscosity decrease in liquids but increase in gases as temperature rises?

In liquids, molecules are closely packed, and viscosity is primarily caused by intermolecular forces holding molecules together. When temperature increases, these molecules gain kinetic energy and move more freely, weakening the attractive forces and reducing viscosity—this is why honey flows easier when heated. In gases, however, molecules are far apart, and viscosity results from momentum transfer during molecular collisions. Higher temperatures increase molecular motion and collision frequency, making it harder for gas layers to slide past each other, thus increasing viscosity.

3. How does viscosity affect engine oil selection and performance?

Viscosity is crucial for engine oil selection because it determines how well the oil lubricates, protects, and flows through the engine at different temperatures. The multi-grade rating system (like 10W-30) indicates viscosity at cold and operating temperatures—the “W” number shows cold-start flow characteristics, while the second number indicates viscosity at engine operating temperature. Too low viscosity means inadequate protection and increased wear, while too high viscosity causes poor cold-start performance, reduced fuel efficiency, and inadequate circulation.

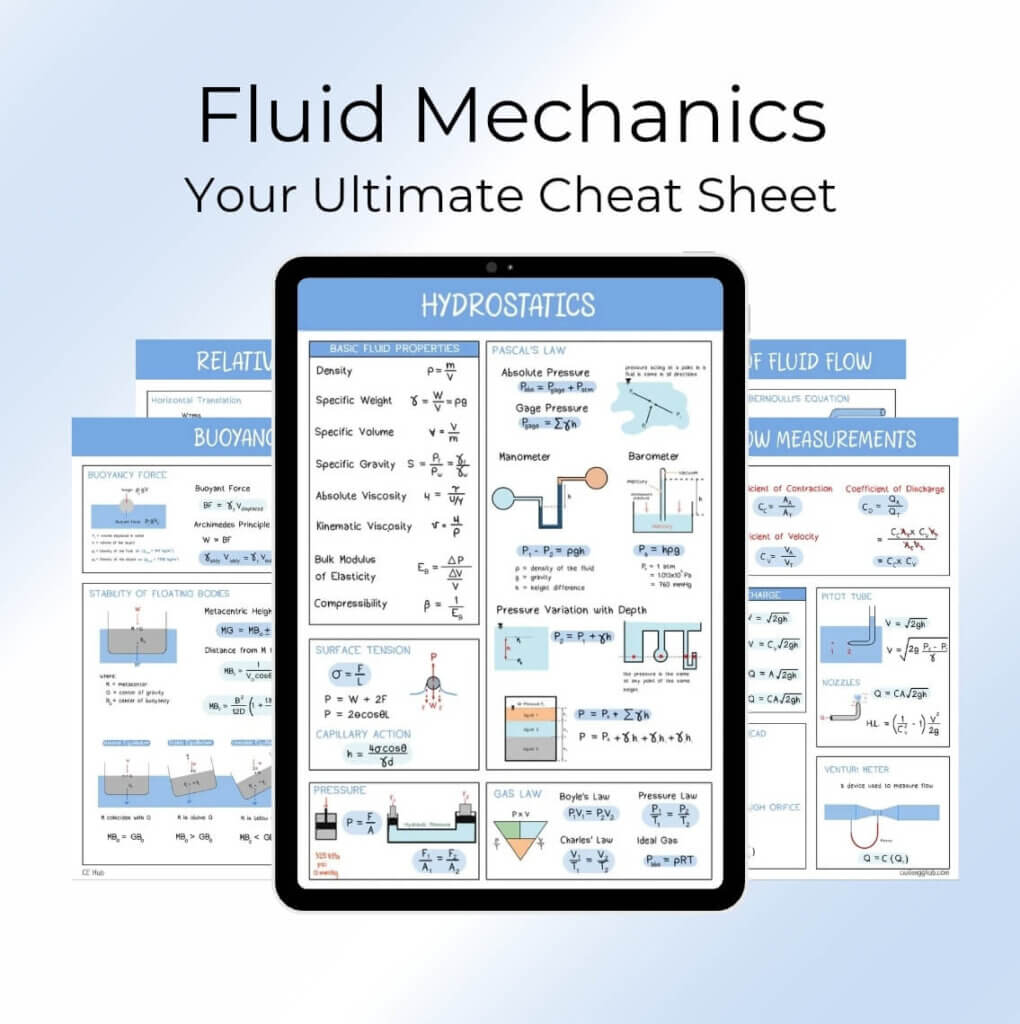

📍This post is part of FLUID MECHANICS COMPLETE Lessons. Also, if you want to avail the complete Cheat Sheet just click the “image” below.